Product Overview

Ethinyl estradiol and desogestrel are used together as a combined oral contraceptive (COC). Ethinyl estradiol is a potent, synthetic estrogen. Desogestrel is a third-generation progestin with lowered androgenic effects and relatively no estrogenic action compared to older progestins. Thus desogestrel may have positive influences on acne, fluid retention, and lipid profiles. Combined hormonal contraceptives can be used in female patients from menarche to over the age of 40 years up until the time of menopause with proper selection of products. The choice of a routine hormonal contraceptive for any given patient is based on the individual’s contraceptive needs, underlying medical conditions or risk factors for adverse effects, and individual preferences for use. All combined oral contraceptives (COCs) have risks related to venous and arterial thromboembolism, particularly in women who smoke; all combined hormonal contraceptive labels contain a boxed warning about tobacco smoking. The Centers for Disease Control’s U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria describe considerations for risk vs. benefits, including medical conditions or attributes that contraindicate use; these criteria can help prescribing practitioners in product selection for individual patients.[1] Contraceptive products containing ethinyl estradiol/desogestrel were initially FDA approved in 1992.[2] Some products provide a reduced hormone-free interval in the cycle, which may be advantageous for patients experiencing migraines, dysmenorrhea, or other symptoms during the days they do not take active hormones.[3]

The primary action of the combination of an estrogen with a progestin is to suppress the hypothalamic-pituitary system, decreasing the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH). Progestins blunt luteinizing hormone (LH) release, and estrogens suppress follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary. Both estrogen and progestin ultimately inhibit maturation and release of the dominant ovule. In addition, viscosity of the cervical mucus increases with hormonal contraceptive use, which increases the difficulty of sperm entry into the uterus. Alteration in endometrial tissues also occurs, which reduces the likelihood of implantation of the fertilized ovum. The contraceptive effect is reversible.[3][2][4] When traditional regimens of oral contraception are discontinued, ovulation usually returns within three menstrual cycles but can take up to 6 months in some women. Pituitary function and ovarian functions recover more quickly than endometrial activity, which can take up to 3 months to regain normal histology.

Both estrogens and progestins are responsible for a number of other metabolic changes. The summary of these changes is dependent on the net actions of the estrogen and progestin combinations. At the cellular level, estrogens and progestins diffuse into their target cells and interact with a protein receptor. Metabolic responses to estrogens and progestins require an interaction between DNA and the hormone-receptor complex. Target cells include the female reproductive tract, the mammary gland, the hypothalamus, and the pituitary. Estrogens increase the hepatic synthesis of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG), thyroid-binding globulin (TBG), and other serum proteins. Estrogens generally have a favorable effect on blood lipids, reducing LDL and increasing HDL cholesterol concentrations. Serum triglycerides increase with estrogen administration. Folate metabolism and excretion is increased by estrogens and may lead to slight serum folate deficiency. Estrogens also enhance sodium and fluid retention. Progestins are classified according to their progestational, estrogenic and androgenic properties. Progestins can alter hepatic carbohydrate metabolism, increase insulin resistance, and have either little to slightly favorable effects on serum lipoproteins. Less androgenic progestins, like desogestrel, have only slight effects on carbohydrate metabolism. More androgenic progestins can aggravate acne. Serious adverse events, like thrombosis, are primarily associated with the estrogen component of hormonal contraceptives but may be the result of both estrogen and progestin components. The mechanism for thrombosis may be associated with increased clotting factor production and/or decreases in anti-thrombin III. Minor side effects can be addressed by choosing formulations that take advantage of relative estrogen, progestin, and androgenic potencies.[5]

Oral contraceptives, like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel, are contraindicated during pregnancy and are labeled FDA pregnancy risk category X.[3] Increased risk of a wide variety of fetal abnormalities, including modified development of sexual organs, cardiovascular anomalies and limb defects, have been reported following the use of estrogens or synthetic progestins alone in pregnant women. With the exception of effects on sexual development, the majority of recent studies do not indicate a teratogenic effect of oral contraceptives when taken inadvertently during early pregnancy. In any patient in whom pregnancy is suspected, pregnancy should be ruled out before continuing oral contraceptive use. Oral contraceptive use may also change folate metabolism, and women who discontinue oral contraceptives to pursue pregnancy should preferably wait 3 months for folate concentrations to normalize if possible. Folate supplementation should be be given once pregnant to reduce the incidence of neural tube defects. Recent studies have found no increased risks of birth defects among women who have inadvertently continued to take birth control pills after they unknowingly became pregnant.

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs) containing ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel are contraindicated in patients with hepatic disease. Because of the association with cholestasis and hepatic neoplasms, estrogens are contraindicated in the presence of hepatocellular cancer, hepatic adenoma, other liver tumors (benign or malignant), or markedly impaired liver function (e.g., uncompensated cirrhosis). Do not use hormonal contraceptives in patients with a history of cholestatic jaundice/pruritus of pregnancy or jaundice from prior hormonal contraceptives; these conditions can recur with subsequent COC use. Discontinue use of ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel if jaundice develops during combined oral contraceptive use. Steroid hormones may be poorly metabolized in patients with liver impairment. Acute or chronic disturbances of liver function may necessitate the discontinuation of COC use until markers of liver function return to normal and COC causation has been excluded. Patients with hepatitis C who are being treated with ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir are also contraindicated to receive COCs. During clinical trials with the hepatitis C combination drug regimen that contains ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir, ALT elevations greater than 5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), including some cases greater than 20 times the ULN, were significantly more frequent in women using ethinyl estradiol-containing medications. Discontinue combined oral contraceptives prior to starting hepatitis C therapy with the combination drug regimen ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir, with or without dasabuvir; COCs can be restarted approximately 2 weeks following completion of treatment with the hepatitis C combination drug regimen. Hepatic adenomas are associated with COC use. An estimate of the attributable risk is 3.3 cases/100,000 COC users. Rupture of hepatic adenomas may cause death through intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Studies have shown an increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma in long-term (more than 8 years) COC users. However, the attributable risk of liver cancers in COC users is less than 1 case per million users. In general, COCs should be used cautiously in patients with pre-existing gallbladder disease and acute or intermittent porphyria.[2][1]

Both progestins and estrogens, like ethinyl estradiol (EE), appear to be excreted into breast milk. Manufacturers recommend avoidance of combined hormonal oral contraceptives (OCs) if possible until a mother has completely weaned her child.[3] Small amounts of oral contraceptive steroids have been identified in the milk of nursing mothers and a few reports of effects on the infant exist, including jaundice and breast enlargement. Other experts often recommend avoidance of estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives, in the first 21 days postpartum (or longer, if other risks for thromboembolism exist) due to maternal post-partum clot risks following obstetric delivery, and the potential for OCs to interfere with the establishment of lactation.[1] It is generally accepted that estrogen-containing combined contraceptives may be used after this period in healthy women without other risk factors; general monitoring of the infant for effects such as appetite changes, breast changes and proper weight gain and growth should occur.[1] Estrogens, including ethinyl estradiol, have been reported to interfere with milk production and duration of lactation in some women, particularly at doses of 30 mcg/day EE or more.[9] One study found that lower dose oral combined contraceptives (e.g., 10 mcg/day EE) may not affect lactation.[10]However, a systematic review concluded that the available evidence, even from randomized controlled trials, is limited and of poor quality; the authors concluded that properly designed and conducted trials are needed to make determinations on the appropriateness of hormonal contraception during lactation and the effects on the health and growth of the infant.[11] However, in general, deleterious effects have not been noted in most infants.[12] Consider the benefits of breastfeeding, the risk of potential infant drug exposure, and the risk of an untreated or inadequately treated condition. If a breastfeeding infant experiences an adverse effect related to a maternally ingested drug, healthcare providers are encouraged to report the adverse effect to the FDA. Alternate contraceptive agents for consideration include non-hormonal contraceptive methods and also progestin-only contraceptives, such as medroxyprogesterone injection (e.g., Depo-Provera).

Preliminary studies have suggested that obesity may be a risk factor for OC failure, particularly with the predominantly lower-dose (i.e., < 50 mcg/day) estrogen formulations available; more studies are needed.[13] Preexisting morbid obesity can also be one factor that may increase cardiovascular or thromboembolic risks associated with combination hormonal contraceptive use, like ethinyl estradiol;desogestrel, in selected individuals. Although the effects appear to be minimal in most non-diabetic patients receiving hormone therapy with estrogen-progestin combinations, altered glucose tolerance secondary to decreased insulin sensitivity has been reported. Patients with hyperglycemia or diabetes mellitus should be observed for changes in glucose tolerance when initiating or discontinuing therapy. Because of the increased potential for embolic risk, combined OCs should be used cautiously in patients with diabetes with vascular involvement. Estrogens generally have a favorable effect on blood lipids, and reduce LDL and increase HDL cholesterol concentrations. Progestins, however, may attenuate some of these effects by raising LDL and may make control of preexisting hyperlipidemia more difficult. Serum triglycerides increase with estrogen administration. A small proportion of women may have persistent hypertriglyceridemia while using combined hormonal contraceptives. Combined hormonal contraceptive agents are contraindicated in patients with a current or past history of stroke, cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, coronary thrombosis, myocardial infarction, thrombophlebitis, thromboembolism or thromboembolic disease, or valvular heart disease with complications. Hormonal combined oral contraceptives (COCs) have been associated with thromboembolic disease such as deep venous thrombosis (DVT). COCs are also generally contraindicated in women who have thrombogenic valvular or thrombogenic rhythm diseases of the heart (e.g., subacute bacterial endocarditis with valvular disease, or atrial fibrillation), or known inherited or acquired hypercoagulopathies (e.g., protein S deficiency, protein C deficiency, Factor V Leiden, prothrombin G20210A mutation, antithrombin deficiency, antiphospholipid antibodies). Because tobacco smoking increases the risk of thromboembolism, DVT, myocardial infarction, stroke and other thromboembolic disease, patients receiving COCs are strongly advised not to smoke. Risk is especially high for female smokers over the age of 35 years or those who smoke 15 or more cigarettes per day. Therefore, COCs are generally considered contraindicated in women over the age of 35 years who are tobacco smokers. A positive relationship between estrogen dosage and thromboembolic disease has been demonstrated, and oral products containing 50-mcg ethinyl estradiol should not be used unless medically indicated. In addition, certain progestins may increase thromboembolic risk. The overall risk of venous thromboembolism in women using COCs has been estimated to be 3 to 9 per 10,000 woman-years. Preliminary data from a large, prospective cohort safety study suggests that the risk is greatest during the first 6 months after initially starting COC therapy or restarting (following a break from therapy 4 weeks or more) with the same or different combination product. The risk of arterial thromboses, such as stroke and myocardial infarction, is especially increased in women with other risk factors for these events. Pre-existing high blood pressure, kidney disease, hypercholesterolemia, hyperlipidemia, morbid obesity, or patients with diabetes with vascular disease may also increase risk. After a COC is discontinued, the risk of thromboembolic disease due to oral contraceptives gradually disappears. Because of their association with elevations in blood pressure, COCs should be used cautiously in patients with mild to moderate hypertension or kidney disease; use is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled or severe hypertension or hypertension with vascular disease. An increase in blood pressure has been reported in women taking COCs, and this increase is more likely in older women and with extended duration of use. The incidence of hypertension increases with increasing concentration of progestin. Blood pressure should be monitored closely in individuals with high blood pressure; discontinue ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel if blood pressure rises significantly. COCs may also cause fluid retention, and patients predisposed to complications from edema, such as those with cardiac or renal disease, should be closely monitored.[2][4][3][1] Approximately 85% of patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are females, giving support to the notion that hormonal influences contribute to the pathophysiology of SLE. Accordingly, oral contraceptive (OC) use has been reported to induce, unmask, and exacerbate lupus; case reports and other anecdotal data indicate that a temporal relationship between OC use and lupus flares exist. However, several retrospective studies dispute a relationship between OCs causing or exacerbating lupus, and a large prospective, randomized clinical trial (SELENA) evaluating the safety of estrogen therapy (both as OCs and hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women) has been completed and is being analyzed. Determining the risk of OC use in SLE patients is important as women with lupus benefit from OCs; not only do they offer reliable birth control, but they also possibly protect patients requiring chronic corticosteroid therapy from bone fractures and osteoporosis. Women with hypercoagulable states are at increased risk of venous thromboembolism when taking OCs; given the increased prevalence of hypercoagulable states in patients with SLE (in particular antiphospholipid antibodies and lupus anticoagulant), presence of a hypercoagulable state should be determined prior to initiation of OCs in this population. OCs should be avoided in SLE patients with a history of venous or arterial thrombosis or the presence of a hypercoagulable state. If OCs are initiated in SLE patients without hypercoagulable states, low-dose estrogen contraceptives (i.e., 30—35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol or equivalent) should be used and consideration to a progestin-only contraceptive should be given. In addition, it may be prudent to avoid OC therapy in patients with unstable or severe SLE or a history of SLE exacerbation with estrogen therapy until more data regarding the use of OCs in this population are available.[14] Patients undergoing elective surgery of a type associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism should usually stop combined hormonal oral contraceptives at least 4 weeks prior and 2 weeks after surgery, dependent upon the continued potential for thromboembolic risk. Combination hormonal contraceptives, like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel, should also be stopped during and after any prolonged immobilization. Ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled hypertension. Because of their association with elevations in blood pressure, hormonal contraceptive agents like combined OCs should be used cautiously in patients with controlled hypertension or kidney disease.[2] Oral products containing 50-mcg ethinyl estradiol should not be used unless medically indicated. Blood pressure should be monitored closely in these individuals. Any significant increase in blood pressure while on hormonal contraceptives may require discontinuation of the medication. Hormonal contraceptives may also cause fluid retention, and patients predisposed to complications from edema should be closely monitored.[15] Ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel is contraindicated in patient with headache, such as migraine that is accompanied by focal neurological symptoms, such as aura.[2] The onset or exacerbation of migraine or the development of headache with a new pattern which is recurrent, persistent or severe requires evaluation of the cause. Mood disorders, like depression, may be aggravated in women taking exogenous hormones. Women with a history of depression may need special monitoring. Low-dose oral contraceptive products may have minimal effect on depressive symptoms. If significant depression occurs, the oral contraceptive, like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel, should be discontinued. Estrogens can increase the curvature of the cornea and may lead to intolerance of contact lenses. Consistent with potential thrombotic effects of oral contraceptives, there have been clinical case reports of retinal thrombosis or retinal vascular occlusion. Any change in vision or visual acuity should be examined by an ophthalmologist, and periodic eye examination is recommended in most patients during oral contraceptive use. Patients developing any unexplained visual disturbance require evaluation; if retinal vascular occlusion occurs, hormonal oral contraception should be discontinued.[2] Long-term oral contraceptive use may play a potential role in the development of glaucoma. According to research presented at a meeting of the American Acadamy of Opthomology, the use of oral contraceptives for > 3 years, irrespective of formulation, was associated with a reported doubling of the incidence of glaucoma. Research data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) included questionnaire responses administered by the Centers for Disease Control. Survey respondents (3406 women, >= 40 years of age) reported on oral contraceptive use between 2005 and 2008; participants completed the survey’s vision and reproductive health questionnaire and underwent eye exams. Women reporting oral contraceptive use for > 3 years were 2.05 times as likely to also report a diagnosis of glaucoma. Although causality was not determined, experts caution patients and providers to be aware of this association and recommend glaucoma screening for patients with additional risk factors. Black patients, patients with a family history of glaucoma, and patients with a history of ocular hypertension or existing visual field defects represent groups with additional risk factors.[16]

The safety and efficacy of hormonal contraceptive products, like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel, have only been established in females of reproductive age. Safety and efficacy of hormonal birth control is expected to be the same for postpubertal children under the age of 16 and for users 16 years of age and older. Use of hormonal contraceptive products in female children before menarche is not indicated.

Ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel is contraindicated in patients with a history of, or known or suspected breast cancer, as breast cancer is a hormonally-sensitive tumor. All women taking combined oral contraceptives (COCs) should receive clinical breast examinations and perform monthly self-examinations as recommended by their health care professional based on patient age, known risk factors, and current standards of care. There is substantial evidence that use of COCs does not increase the incidence of breast cancer. Although some past studies have suggested that COCs might increase the incidence of breast cancer, more recent studies have not confirmed such findings.[3][2] [4] Several large, well designed observational studies have provided data regarding the risk of breast cancer with combined oral contraceptive (COC) use.[17][18][19][20] From one large study published in 2017, the risk of breast cancer was higher among women who currently or recently used contemporary hormonal contraceptives than among women who had never used hormonal contraceptives, and this risk increased with longer durations of use; however, absolute increases in risk were small. The absolute risk of breast cancer associated with any hormonal contraceptive use was 13 per 100,000 women-years, which corresponds to 1 extra case of breast cancer for every 7,690 COC users in 1 year.[21] Moreover, the same study data suggest that any increased risk of breast cancer usually disappears rapidly after an interruption in the use of COCs.[21] There continues to be controversy regarding the risk of COC use in women with a family history of breast cancer (e.g., BRCA mutations). However, evidence does not suggest that the increased risk for breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes is modified by the use of COCs.[1] Patients should be instructed to perform monthly self-breast examination and report any breast changes, lumps, or discharge to their health care professional. If breast cancer is suspected in a woman who is taking hormonal contraceptives, the contraceptive should be discontinued.[1]

Estrogen-progestin combinations are not recommended in patients with hypercalcemia associated with tumors or metabolic bone disease because estrogens influence the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus.

Ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel is contraindicated in the presence of cervical cancer or other estrogen-responsive tumors. Most cervical cancers are related to the presence of the human papillomavirus (HPV), but hormonal factors influence risk. In women taking COCs, studies have found a slightly increased risk of cervical cancer compared with never-users. The risk appears to increase with duration of use and appears to decline when COCs are discontinued. Clinical surveillance of all women using COCs is important; all women receiving COC treatment should have an annual pelvic examination and other diagnostic or screening tests, such as cervical cytology, as clinically indicated or as generally recommended based on age, risk factors, and other individual needs.[20][2][3][4]

In those women with known endometrial cancer or other estrogen-dependent tumors (e.g., vaginal cancer, uterine cancer, ovarian cancer), combined hormonal contraceptives are contraindicated, as such tumors are hormonally sensitive. Hormonal contraceptives are contraindicated in women with undiagnosed vaginal bleeding; evaluate such patients before combined hormonal contraceptive use to determine if a contraindication to use exists.[1][3][2][4] The use of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) appears to have a protective effect against some cancers. In women using COCs, a meta-analysis of 10 studies indicates a significant trend in decreasing endometrial and ovarian cancer risk with increasing duration of COC use. The beneficial effects of COCs in this regard may persist for 15 years or more after COC use ceases. [1][20]

Use estrogens with caution in patients with thyroid disease, particularly hypothyroidism. Estrogens can increase thyroid-binding globulin (TBG) levels. Patients with normal thyroid function can compensate for the increased TBG by making more thyroid hormone, thus maintaining free T4 and T3 serum concentrations in the normal range. Patients dependent on thyroid hormone replacement therapy who are also receiving estrogens may require increased doses of their thyroid replacement therapy. These patients should have their thyroid function monitored in order to maintain their free thyroid hormone levels in an acceptable range.

Chloasma or melasma may occasionally occur, especially in women with a history of chloasma gravidarum.[3] Women with a tendency for chloasma should avoid sunlight (UV) exposure while taking ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel.

Cases of both anaphylactic reactions and angioedema have been reported in patients taking exogenous estrogens. Events have developed in minutes and have required emergency medical treatment. Ethinyl estradiol is generally contraindicated in patients who have a history of anaphylaxis or history of angioedema to the drug. In addition, exogenous estrogens may induce or exacerbate symptoms of angioedema, particularly in women with hereditary angioedema, which may be hormonally sensitive.

Breakthrough bleeding and spotting are sometimes encountered, especially during the first 3 months of oral contraceptive use such as ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel. Change in menstrual flow (menstrual irregularity) and amenorrhea have also been reported and are believed to be drug-related. In the event of breakthrough vaginal bleeding, consider nonhormonal causes and take adequate diagnostic measures to rule out malignancy or pregnancy. If pathology has been excluded, time or a change to another formulation may solve the problem. In the event of amenorrhea, rule out pregnancy. Some women may encounter post-pill amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea, especially when such a condition was pre-existent.[2] Other adverse effects may include dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and pelvic pain.

Breast tenderness or mastalgia, breast enlargement, and breast discharge or secretion have been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives such as ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel and are believed to be drug-related.[2] Galactorrhea and lactation suppression may also occur.

Vaginal discharge (leukorrhea) or vaginal irritation due to candidiasis or vaginitis can occur during therapy with hormonal contraceptive agents like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel.[2]

Oral contraceptives (e.g., ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel) are associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic and thrombotic disease. The risk for the development of deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism is approximately 3—6 times greater in OC users than in nonusers. In several studies, the risk was reported to be higher in smokers compared with nonsmokers. The relative risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in women who have predisposing conditions is twice that of women without such medical conditions. The risk of VTE due to oral contraceptive use gradually disappears after the combined hormonal contraceptive is discontinued. VTE risk is highest in the first year of use and when a combination oral contraceptive is started or re-started after a break in use of four weeks or more.[1] Stop ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel if an arterial or venous thrombotic event occurs.[2] Both hormone amount and hormone type may be important factors regarding rates of thromboembolic disorders. Estrogens decrease levels of antithrombin-III and increase the production of blood clotting factors VII, VIII, IX and X; risks increase with ethinyl estradiol doses > 50 mcg/day. Women who took OCs containing certain types of progestin (e.g., desogestrel or gestodene) had an increased risk (adjusted RR = 1.9) for nonfatal VTE compared with women who took OCs containing levonorgestrel.[24588] However, association of increases in VTE risk with newer progestins cannot be proved due to limitations and inconsistencies in the results of several of these observational studies. No consistent differential effects on hemostasis with the newer progestins ( e.g., desogestrel, gestodene) have been established versus older progestins.

Oral contraceptives may cause edema (fluid retention) and, thus, weight gain. Appetite stimulation may also occur. An increased risk of hypertension and of myocardial infarction has been associated with the use of oral contraceptives such as ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel. An increase in blood pressure is more likely in older oral contraceptive users and with continued use. The incidence of hypertension increases with increasing concentrations of progestogens. Close monitoring of blood pressures is recommended for patients at risk for hypertension; discontinue ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel if significant elevation of blood pressure occurs. Blood pressures usually return to normal after discontinuation of therapy, and no difference in the occurrence of hypertension exists among ever- and never-users. Myocardial infarction risk is primarily in smokers or women with other underlying risk factors for coronary artery disease such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, morbid obesity, and diabetes. Oral contraceptives may compound the effects of well-known risk factors. In particular, some progestogens are known to decrease HDL cholesterol and cause glucose intolerance, while estrogens may create a state of hyperinsulinism. The relative risk of heart attack for current oral contraceptive users has been estimated to be 2 to 6.2. The risk is very low under the age of 30. However, there is the possibility of a risk of cardiovascular disease even in very young women who take oral contraceptives. Smoking in combination with oral contraceptive use has been shown to contribute substantially to the incidence of myocardial infarctions in women in their mid-thirties or older, with smoking accounting for the majority of excess cases. Mortality rates associated with circulatory disease have been shown to increase substantially in smokers over the age of 35 and non-smokers over the age of 40 among women who use oral contraceptives.[2]

An increase in both the relative and attributable risks of cerebrovascular events (thrombotic and hemorrhagic strokes) has been shown in users of oral contraceptives such as ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel. In general, the risk is greatest among older (> 35 years), hypertensive women who also smoke. Hypertension was found to be a risk factor for both users and non-users for both types of strokes while smoking interacted to increase the risk for hemorrhagic strokes. In a large study, the relative risk of thrombotic strokes has been shown to range from 3 for normotensive users to 14 for users with severe hypertension. The relative risk of hemorrhagic stroke (intracranial bleeding) is reported to be 1.2 for non-smokers who used oral contraceptives, 2.6 for smokers who did not use oral contraceptives, 7.6 for smokers who used oral contraceptives, 1.8 for normotensive users, and 25.7 for users with severe hypertension. The attributable risk also is greater in women in their mid-thirties or older and among smokers.[2] Regarding stroke and OC use, risk may be related to the amount of estrogen as well as the type of progestin, although this issue is controversial. Early epidemiological studies showed an increased risk for stroke, as well as MI and venous thromboembolism, however these studies assessed OCs containing more than 50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol. Use of OCs containing lower amounts of estrogen (i.e., <= 35 mcg ethinyl estradiol) has not been associated with an overall increased risk of stroke in more recent studies. Conflicting data exist, however, regarding the association of OC use and hemorrhagic stroke. In one study, norgestrel-type progestins (e.g., levonorgestrel) were associated with a higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke (odds ratio = 3.28) compared with non users of OCs.[23] Another study, however, showed no increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in users of levonorgestrel-containing OCs.[24] Therefore, although the risk of stroke in users of OCs appears to be related to estrogen amount (i.e., increased risk has been demonstrated with products containing >= 50 mcg but not for products containing <= 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol), further studies are needed to clarify the relationship of type of progestin to risk of stroke in users of OCs. Clinical case reports of retinal thrombosis associated with the use of oral contraceptives exist. Optic neuritis, which may lead to partial or complete loss of vision has been reported in users of oral contraceptives, however the association has been neither confirmed nor refuted. Likewise, cataracts have been reported during oral contraceptive use without evidence of causality.[25] Exogenous estrogen use can cause a conical cornea to develop from steepening or increased curvature of the cornea, caused by thinning of the stroma. Patients with contact lenses may develop intolerance to their lenses. Any change in vision or visual acuity should be examined by an ophthalmologist. In the event of unexplained visual impairment, onset of proptosis or diplopia, papilledema, or retinal vascular lesions, discontinue ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel. Immediately take appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures.[2] Depression has been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives such as ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel and is believed to be drug-related. In addition to depression, nervousness or anxiety, libido decrease, libido increase, emotional lability, fatigue, asthenia, and irritability have been reported.[2] Carefully observe women with a history of depression. Discontinue ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel if depression recurs to a serious degree. Also, stop ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel in patients who become significantly depressed to try to determine whether the depression is drug related. Headache is a common adverse effect of oral contraceptives. Migraine has been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives such as ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel and is believed to be drug-related. A number of changes can occur when a woman initiates oral contraceptive therapy and include 1) migraines can appear for the first time, 2) a change in frequency, severity, and duration of migraine headaches may be seen, or 3) an improvement or decrease in the occurrence of migraine headaches. When initiating therapy, observe an individual's migraine pattern. The onset or exacerbation of migraine or development of headache with a new pattern that is recurrent, persistent, or severe requires discontinuation of oral contraceptives and evaluation of the cause.[2] Maculopapular rash, rash (unspecified), pruritus, anaphylactic or anaphylactoid reactions, urticaria, angioedema, and melasma are believed to be related to oral contraceptives like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel. Melasma, in the form of tan or brown patches, may develop on the forehead, cheeks, temples and upper lip. These patches may persist after the drug is discontinued. Photosensitivity can be experienced with oral contraceptive use and protective clothing and sunscreens should be employed when exposed to sunlight or UV light. An association of oral contraceptives with acne vulgaris, hirsutism, alopecia, erythema multiforme, or erythema nodosum has been neither confirmed nor refuted. Although oral contraceptives can be used to treat acne vulgaris, in some cases they may induce or aggravate existing acne.[2] Some women taking oral contraceptives, like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel, notice tenderness, swelling, or minor bleeding of their gums, which may lead to gingivitis. Proper attention to oral care and regular dental visits are recommended. Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or cramps, bloating, and cholestatic jaundice have been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives and are believed to be drug-related. Abdominal pain can indicate cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, cholestasis, pancreatitis, or peliosis hepatis. An increased risk of gallbladder disease is associated with oral contraceptive use, but the risk may be minimal, especially with the use of oral contraceptive formulations that contain lower hormonal doses of estrogens and progestogens. In patients with familial defects of lipoprotein metabolism receiving estrogen-containing preparations, significant elevations of plasma triglycerides (hypertriglyceridemia) leading to pancreatitis have been reported. Numerous cases of bowel ischemia (ischemic colitis) have been reported during combined estrogen and progesterone use; mesenteric vein thrombus due to hypercoagulability is the proposed mechanism.[26] Other adverse effects may include colitis, elevated hepatic enzymes, hepatitis, hyperlipidemia, diarrhea, dyspepsia, anorexia, weight loss, and Budd-Chiari syndrome or hepatic vein obstruction. Peliosis hepatis, a very rare consequence of taking estrogens and combined oral contraceptives, is characterized by the presence of blood-filled spaces.[27] In rare cases, oral contraceptives can cause benign but dangerous liver tumors. Indirect calculations have estimated the attributable risk of hepatoma to be in the range of 3.3 cases per 100,000 for users, a risk that increases after 4 or more years of use. These benign liver tumors can rupture and cause fatal internal bleeding.[2] Discontinue ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel if jaundice develops, as steroid hormones may be poorly metabolized in patients with impaired liver function. Cholestatic jaundice of pregnancy or jaundice with prior pill use are contraindications for ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel use. The issue of hormonal influences on the development of cancers (new primary malignancy) has been widely researched for many decades. Most studies have been performed with combined oral contraceptives (COCs), and the risks related to combined hormonal contraceptives, regardless of route of administration, are thought to be similar. In general, the data suggest an increased risk of cervical cancer among combined oral contraceptive (COC) users, with a decreased risk for endometrial and ovarian cancers. BREAST CANCER: There is substantial evidence that use of COCs does not significantly increase the incidence of breast cancer. Although some past studies have suggested that COCs might increase the incidence of breast cancer, more recent studies have not confirmed such findings.[3][2][4][21] Several large, well designed observational studies have provided data regarding the risk of breast cancer with combined oral contraceptive (COC) use.[17][18][19]Breast cancers diagnosed in current or previous COC users tend to be less advanced clinically than in never-users. The risk of breast cancer is only slightly increased in current and recent COC users (i.e., within 10 years); however, 10 years after COC cessation, the risk of breast cancer appears to be similar to that in those patients that have never used COCs.[20] From one large study published in 2017, the risk of breast cancer was higher among women who currently or recently used contemporary hormonal contraceptives than among women who had never used hormonal contraceptives, and this risk increased with longer durations of use; however, absolute increases in risk were small. The absolute risk of breast cancer associated with any hormonal contraceptive use was 13 per 100,000 women-years, which corresponds to 1 extra case of breast cancer for every 7,690 COC users in 1 year.[21] Moreover, the same study data suggest that any increased risk of breast cancer usually disappears rapidly after an interruption in the use of COCs.[21] There continues to be controversy regarding the risk of COC use in women with a family history of breast cancer (e.g., BRCA mutations). However, evidence does not suggest that the increased risk for breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes is modified by the use of COCs.[1] Patients should be instructed to perform monthly self-breast examination and report any breast changes, lumps, or discharge to their health care professional. If breast cancer is suspected in a woman who is taking hormonal contraceptives, the contraceptive should be discontinued.[3][2][4] CERVICAL CANCER: Some studies suggest that COC use has been associated with an increase in the risk of cervical cancer or intraepithelial neoplasia; however, such findings may be due to differences in sexual behavior, presence of the human papilloma virus (HPV) and other factors. HPV is thought to be the cause of more than 90% of all cervical cancers, although, hormonal factors may influence risk. The relative risk of invasive cervical cancer of 1.37 after 4 years of use; relative risk increased to 1.6 after 8 years of use. Because a potential for cervical dysplasia may exist, regularly evaluate patients taking COCs via cervical cytology screening as recommended per standards of care.[20] OTHER CANCERS: A meta-analysis of 10 studies indicated significant trends for a reduced risk for endometrial and ovarian cancer with increased duration of COC use. Risk of endometrial or ovarian cancers may be reduced by up to 60% with 4 or more years of use. Data suggest COCs do not protect against hereditary forms of ovarian cancer (e.g., women who carry BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene alterations).[25199] Studies have shown an increased risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma in long-term (more than 8 years) COC users. However, these cancers are rare in the United States, and the attributable risk (the excess incidence) of liver cancers in oral contraceptive users approaches less than 1 per million users.[20][3][2][4] Myalgia, arthralgia, back pain, systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus-like symptoms), and musculoskeletal pain have been noted with oral contraceptives such as desogestrel; ethinyl estradiol. Rhinitis and sinusitis have been noted with oral contraceptives such as desogestrel; ethinyl estradiol. Cystitis has been noted with oral contraceptives such as desogestrel; ethinyl estradiol. Porphyria has been noted with oral contraceptives such as desogestrel; ethinyl estradiol.

Oral contraceptives, like ethinyl estradiol; desogestrel, are contraindicated during pregnancy and are labeled FDA pregnancy risk category X.[3] Increased risk of a wide variety of fetal abnormalities, including modified development of sexual organs, cardiovascular anomalies and limb defects, have been reported following the use of estrogens or synthetic progestins alone in pregnant women. With the exception of effects on sexual development, the majority of recent studies do not indicate a teratogenic effect of oral contraceptives when taken inadvertently during early pregnancy. In any patient in whom pregnancy is suspected, pregnancy should be ruled out before continuing oral contraceptive use. Oral contraceptive use may also change folate metabolism, and women who discontinue oral contraceptives to pursue pregnancy should preferably wait 3 months for folate concentrations to normalize if possible. Folate supplementation should be be given once pregnant to reduce the incidence of neural tube defects. Recent studies have found no increased risks of birth defects among women who have inadvertently continued to take birth control pills after they unknowingly became pregnant.

Both progestins and estrogens, like ethinyl estradiol (EE), appear to be excreted into breast milk. Manufacturers recommend avoidance of combined hormonal oral contraceptives (OCs) if possible until a mother has completely weaned her child.[3] Small amounts of oral contraceptive steroids have been identified in the milk of nursing mothers and a few reports of effects on the infant exist, including jaundice and breast enlargement. Other experts often recommend avoidance of estrogen-containing hormonal contraceptives, in the first 21 days postpartum (or longer, if other risks for thromboembolism exist) due to maternal post-partum clot risks following obstetric delivery [1], and the potential for OCs to interfere with the establishment of lactation. It is generally accepted that estrogen-containing combined contraceptives may be used after this period in healthy women without other risk factors; general monitoring of the infant for effects such as appetite changes, breast changes and proper weight gain and growth should occur.[1] Estrogens, including ethinyl estradiol, have been reported to interfere with milk production and duration of lactation in some women, particularly at doses of 30 mcg/day EE or more.[9] One study found that lower dose oral combined contraceptives (e.g., 10 mcg/day EE) may not affect lactation.[10]However, a systematic review concluded that the available evidence, even from randomized controlled trials, is limited and of poor quality; the authors concluded that properly designed and conducted trials are needed to make determinations on the appropriateness of hormonal contraception during lactation and the effects on the health and growth of the infant.[22] However, in general, deleterious effects have not been noted in most infants.[12] Consider the benefits of breast-feeding, the risk of potential infant drug exposure, and the risk of an untreated or inadequately treated condition. If a breast-feeding infant experiences an adverse effect related to a maternally ingested drug, healthcare providers are encouraged to report the adverse effect to the FDA. Alternate contraceptive agents for consideration include non-hormonal contraceptive methods and also progestin-only contraceptives, such as medroxyprogesterone injection.

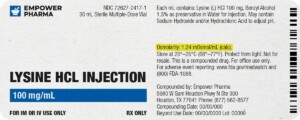

Store this medication at 68°F to 77°F (20°C to 25°C) and away from heat, moisture and light. Keep all medicine out of the reach of children. Throw away any unused medicine after the beyond use date. Do not flush unused medications or pour down a sink or drain.

- US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

- Desogen (desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol) package insert. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck Sharp and Dohme Corp; 2017 Aug.

- Mircette (desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol) oral contraceptive package insert. North Wales, PA: TEVA Pharmaceuticals; 2017 May.

- Cyclessa (desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol) triphasic oral contraceptive package insert. Whitehouse Station, NJ: NV Organon and Organon USA; 2017 Aug.

- Brunton LB, Lazo JS, Parker KL, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

- Chang SY, Chen C, Yang Z, et al. Further assessment of 17alpha-ethinyl estradiol as an inhibitor of different human cytochrome P450 forms in vitro. Drug Metab Dispos 2009;37:1667-75.

- Zhang H, Cui D, Wang B, et al. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions involving 17alpha-ethinylestradiol: a new look at an old drug. Clin Pharmacokinet 2007;46:133-57.

- Kim WY, Benet LZ. P-glycoprotein (P-gp/MDR1)-Mediated Efflux of Sex-Steroid Hormones and Modulation of P-gp Expression In Vitro. Pharmaceutical Research 2004;21:1284.

- Tankeyoon M, Dusitsin N, Chalapati S, et al. Effects of hormonal contraceptives on milk volume and infant growth. WHO Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, Task Force on Oral Contraceptives. Contraception. 1984;30:505–522.

- Toddywalla VS , Joshi L, Virkar K. Effect of contraceptive steroids on human lactation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1977;127:245-249.

- Truitt ST, Fraser AB, Grimes DA, et al. Hormonal contraception during lactation. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception. 2003;68:233-238.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committee on Drugs. Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 2001;108(3):776-789.

- Holt VL, et al. Body weight and risk of oral contraceptive failure. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:820-827.

- Askanase AD. Estrogen therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Treat Endocrinol 2004;3:19-26.

- Ortho-cept (desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol) package insert. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceutical, Inc.; 2015 Nov.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology press release. November, 18 2013. Long-Term Oral Contraceptive Users are Twice as Likely to Have Serious Eye Disease. Available on the World Wide Web at: http://www.aao.org/newsroom/release/oral-contraceptives-increase-glaucoma-risk.cfm#_edn1

- The Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study of the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Oral Contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 1986;315:405-411.

- Collaborative Group of Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet 1996;347:1713-27.

- Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. Oral contraceptives and the risk of breast cancer. [Women’s Contraceptive and Reproductive Experiences (Women’s CARE) Study]. N Engl J Med 2002;346:2025-2032.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. COMBINED ESTROGEN–PROGESTOGEN CONTRACEPTIVES. In: Pharmaceuticals. Lyon, France: a publication of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC);2012;100A:283-311. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304334

- Morch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, et al. Contemporary Hormonal Contraception and the Risk of Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:2228-2239.

- Truitt ST, Fraser AB, Grimes DA, et al. Hormonal contraception during lactation. . Systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception. 2003;68:233-238.

- Schwartz SM, Siscovisk DS, Longstreth WT, et al. Use of low-dose oral contraceptives and stroke in young women. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:596-603.

- Petitti DB, Sidney S, Bernstein A, et al. Stroke in users of low-dose oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med 1996;335:8-15.

- Loestrin FE 1/20 and 1.5/30 (norethindrone acetate and ethinyl estradiol) package insert. Lake Wales PA: TEVA Pharmaceuticals; 2017 Aug.

- Cappell MS. Colonic toxicity of administered drugs and chemicals. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1175-90.

- Radzikowska E, Maciejewski R, Janicki K, et al. The relationship between estrogen and the development of liver vascular disorders. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2001;56:189-93.

503A vs 503B

- 503A pharmacies compound products for specific patients whose prescriptions are sent by their healthcare provider.

- 503B outsourcing facilities compound products on a larger scale (bulk amounts) for healthcare providers to have on hand and administer to patients in their offices.

Frequently asked questions

Our team of experts has the answers you're looking for.

A clinical pharmacist cannot recommend a specific doctor. Because we are licensed in all 50 states*, we can accept prescriptions from many licensed prescribers if the prescription is written within their scope of practice and with a valid patient-practitioner relationship.

*Licensing is subject to change.

Each injectable IV product will have the osmolarity listed on the label located on the vial.

Given the vastness and uniqueness of individualized compounded formulations, it is impossible to list every potential compound we offer. To inquire if we currently carry or can compound your prescription, please fill out the form located on our Contact page or call us at (877) 562-8577.

We source all our medications and active pharmaceutical ingredients from FDA-registered suppliers and manufacturers.

We're licensed to ship nationwide.

We ship orders directly to you, quickly and discreetly.